Claude, Seaport With the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648. Nat Gall

Turner, Dido Building Carthage, 1815. National Gallery

So my question to the Gallery is: how real was the connection between the 17th century Frenchman who lived in Italy … and the 19th century Englishman who loved Claude’s work, even before he made his first visits to France, Switzerland and Italy?

The longer Claude lived in Italy, the more his paintings became classical, monumental and sensitive to the effects of light. One of his important mid-life paintings was Seaport With the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, painted in 1648. Many of Claude's paintings were concerned with travel, but here he created an imaginary seaport to depict the unusual story of Sheba’s and Solomon’s separation. The classical architecture was stunning, dwarfing the human beings and even dwarfing the ships.

I believe that during the Italian decades, Claude was always Claude. So the comparison between the two artists stands or falls on which Turners were selected. Country Life 21/3/2012 aptly chose the National Gallery’s own Dido Building Carthage 1815, identifying it as one Turner’s most direct salutes to Claude. The seascape was also concerned with an imaginary seaport, with ancient architecture and human beings, but this time the sky was hazier and the water darker than in Claude’s vision.

Turner, Waves Breaking on a Lee Shore at Margate c1840. Tate

Turner’s later painting Waves Breaking on a Lee Shore at Margate c1840 (Tate London) was a very different kettle of fish, owing nothing to Claude. Instead of classical ruins, depicted in minute detail and lit by a pale blue sky, Turner’s drama came from an extremely rough sea. The sky above looked ominous and in the distant coast, the viewer could almost detect the outlines of the town’s harbour wall and lighthouse. Turner no longer bothered with minutely depicted architecture, classical or otherwise. The wild sea and sky were now his subjects.

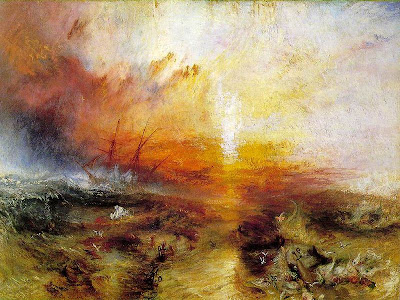

Turner, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, 1840, Boston MFA