When Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) was 3 years old, the family moved to Vienna and Paris, so Gertrude spoke German, French and English from childhood. Her father then moved the family back to the USA in 1879 but died suddenly in 1891, so the oldest brother Michael had to sustain the whole family.

Another brother, Leo Stein, moved back to Europe, painting and immersing himself in art in Florence. In 1903 Gertrude also moved back to Europe. She eventually ended up in Paris, with Leo, at a painting studio at 27 Rue de Fleurus on the left bank. Their large independent income, which Michael and his wife Sarah sent each month, made a bohemian life-style in Paris easy to sustain.

How did the Leo and Gertrude Stein become so knowledgeable about art? Art scholar Bernard Berenson introduced Leo to Paul Cézanne and helped Leo buy an early work from Ambroise Vollard's gallery. In 1904 Berenson took both Steins under his wing in Florence.

I have lectured many times on the Steins as cultural salonieres, but the

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is now suggesting that the family was more important as art collectors. I may change my mind, but I doubt it.

Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905, San Francisco Museum of ArtIn 1905 Leo and Gertrude saw the Manet Retrospective in Paris and bought

Portrait of a Woman with a Hat by Henri Matisse. This purchase encouraged Matisse at a crucial point in his art development. It was at a time when he and other avant-garde artists were being criticised by the press. Soon the Steins were visiting the Matisses socially.

In 1905 Pablo Picasso met the Steins at Clovis Sagot’s, who had turned a pharmacy into an informal art gallery. Soon after, the first Picasso oil paintings that Leo bought was

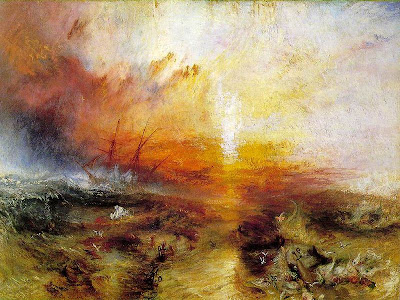

Nude on a Red Background, a rose-period nude of a girl. Then the Steins bought some works of Renoir, two Gauguins, a Daumier, a Delacroix, an El Greco and some Cézanne water colours.

The friendship with the Matisses cooled only when Gertrude developed a much greater interest in Picasso. But all was well since it was actually Michael and Sarah Stein who continued to collect Matisses in particular.

Etta and Claribel Cone were two wealthy, elegant, educated Baltimore women. Etta inherited her wealth at 27, giving her a handsome yearly income to spend. The Steins and Cones all travelled to Florence in1905 where Bernard Berenson introduced the Cones to art by Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck and Friesz. The Steins took Etta to meet Picasso at his studio while he was doing Gertrude's portrait, and persuaded Etta to buy Picasso drawings whenever that artist was short of funds.

Back left: Leo and Gertrude Stein, back right = Sarah and Michael Stein, 27 rue de Fleurus, Paris, c1905.

The Steins were introducing artist to artist, patron to artist, patron to patron. In 1905/6, Leo and Gertrude invited Picasso and Matisse to their studio to meet each for the first time. In Jan 1906, Michael and Sarah Stein took Etta and Claribel to meet Matisse at his apartment over the Seine, and both sisters bought as many paintings and drawings as they could afford. Gertrude also sold the Cones a number of her prized pictures including Delacroix, Cézanne and a group portrait by Marie Laurencin that showed several of the regulars of the Stein salon, including Picasso.

Baltimore ultimately benefitted from the Cones' collecting.

27 Rue de Fleurus became the first real and permanent home for the Steins, and one that Gertrude remained in for 40 years. This is where the Steins provided the informal focal point for contemporary art in Paris. They inspired, supported and, most importantly for the modernists, they bought art. Their home became known as a salon, with paintings covering all the wall space in their home. Works by Picasso, Renoir, Gauguin, Cezanne and others overflowed into every room of the household. Artists, writers and critics became frequent callers, for the Saturday night art parties.

Michael and Sarah Stein also held open house on Saturday nights, near the younger Steins, and the participants could move easily fromone home to the other. These evenings enabled the young, impoverished artists to examine the family’s notable collections of paintings by good artists. Their salons functioned as galleries.

Picasso, Nude on a Red Background, 1906, Musée de l'Orangerie ParisBy 1909, photographer/gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz was introduced to the Steins. By this time Stieglitz was well acquainted with the works of Matisse, Picasso, and Cezanne, and began to actively negotiate with Leo and Gertrude to exhibit their massive art collection in his gallery. Other young modernist painters eg Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, Marie Laurençin, Robert Delaunay, as well as Guillaume Apollinaire, frequented their salon.

Gertrude understood the radical implications of Cubism and was prepared to associate her reputation with it. Spanish cubist Juan Gris frequently visited in the 1910s, finding Stein accepting of the more radical art styles that other people tended to reject out of hand.

For the newly arrived young Jewish artists from Eastern Europe, starving in their Paris garrets, the Steins’ salons filled with food and drink were also much appreciated. The Steins and Cones might have all been secularist Jews, but they went out of their way to help young Jewish artists arriving weekly from Eastern Europe, especially Max Weber, sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, Chaim Soutine, Sonia Delauney and Italian Amedeo Modigliani.

The fact that all the Steins, the Cone sisters, Alfred Stieglitz, Man Ray, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Alice B Toklas all spoke Yiddish or German as their mother tongue must have helped the young Eastern Europeans integrate, during their first difficult years in Paris. And, let me repeat, the endless supply of food and wine!

Alice B Toklas decided to sail from the USA to Europe and while in Paris, she was invited to a Saturday night party at #27. Toklas was soon besotted. She soon became a regular visitor and began going to the galleries and theatre with Gertrude. In 1910 Alice moved into the rue de Fleurus household and became Gertrude's right hand woman, secretary, reader and critic.

But several years after Alice arrived, there was a family rupture. Leo was a dedicated Matisse patron, not a fan of Cubism. Gertrude and Alice visited Pablo Picasso at his studio where he was at work on

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Les Demoiselles was the work that marked the beginning of the end of Leo's support for Picasso. In 1912, Gertrude and Alice took all the Picassos, Leo the Renoirs and many of the Cézannes. Leo moved to Italy, permanently!

Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas in their art salon, rue de Fleurus.The Steins had established the first “museum” of modern art. But the salon wound down with war breaking out in 1914, when Gertrude and Alice moved to Spain. However Gertrude still befriended people like writer Ernest Hemingway and designer Jean Cocteau. And Gertrude was still in close contact with Claribel Cone who happened to be in Munich when WWI broke out.

On her return to Baltimore in 1921, Claribel rented a large apartment in the same building as Etta’s and arranged it as a private museum for their growing collection. The excellent Cone collection of art eventually entered the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Claribel Cone died in 1929, Leo Stein died in 1947, Gertrude Stein died in 1946 and Alice B Toklas in 1967. Gertrude and Alice B Toklas were both buried in Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

The recent San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's exhibition brought together important and difficult-to-assemble paintings that haven’t been together since pre-WW1 Paris. The Stein collection had been divided and subdivided constantly among relative, friends, dealers and collectors. Gertrude and Leo traded back pictures to acquire new ones, a practice that made it difficult to track down their possessions. American collectors John Quinn and Albert Barnes both had access to the Stein salon and acquired significant paintings from them. In 1913, Gertrude traded large early Picassos to dealer Kahnweiler in exchange for other paintings she wanted. Thus I am convinced the Steins were hugely successful as salonieres and patrons, but in the long term less successful as collectors of art.

I hope people fascinated with the Paris salon saw

The Steins Collect Matisse, Picasso and the Parisian Avant-Garde exhibition at the San Francisco MoMA, May - September 2011. Second best would be getting hold of the catalogue.

National Gallery of Victoria, front entrance

National Gallery of Victoria, front entrance